How Big Oil saved Reston’s radical vision

The master-planned town is celebrating its 60th anniversary. It owes an unlikely ally.

The Fairfax Time Machine, a new column debuting here, will take readers back to explore local stories from the past that resonate today. Have a timely idea for a future one? Drop me a note.

It was the fall of 1967, and the new town of Reston was on the brink.

Its too-modern townhouses weren’t selling. Its development was lagging. And its founder, Robert E. Simon Jr., was running dry on cash faster than investors — who for years were skeptical of his master-planned, European-inspired, racially integrated community — were infusing it.

The proposal “was so unusual for Northern Virginia at that time,” said Shelley Mastran, a board member at the Reston Museum. “A lot of lenders just looked at this architecture, townhouses in the middle of nowhere, and said, ‘This is not a solid investment.’”

But Simon’s unlikeliest partner risked it. Gulf Oil already had rescued Reston once and now, in September 1967, gave it a final financial lifeline. This one would end with Simon exiled back in New York, abruptly booted from his own project.

It also would end, to the surprise of national observers and the town’s first residents alike, with two of the world’s largest oil and gas companies building Reston into just about what Simon had envisioned.

“It was Gulf and Mobil that basically made Reston Reston,” said Chuck Veatch, an early salesman under Simon who has worked in Reston real estate ever since. “First Gulf and then Mobil basically stuck with the master plan for the development of Reston, and they had the money to do it. They had the money to pull it off.”

Simon had had money, too. It just couldn’t meet all that radical Reston, which celebrates its 60th anniversary this weekend, turned out to cost.

Sold on a vision

The son of a New York real-estate executive, Simon had taken over the family business early in his 20s, fortified with a Harvard education and a perspective shaped by Italian plazas, the mingling of arts and business on 57th Street, and a suburban commuter lifestyle he resented on Long Island.

His company’s prized property was New York’s then-ailing Carnegie Hall. In 1960, Simon sold it to the city to preserve, for $5 million. He needed to spend the windfall quickly to avoid a tax hit, the Washington Post later wrote, and he ruminated on a community that might marry the best of urban and rural life:

Access to employment and leisure.

Beauty in nature and architecture.

People-first planning, with spaces to congregate.

A meld of residents by age, race and income.

The ability to live one’s life there start-to-finish.

Months after the Carnegie Hall sale, a broker pitched Simon on hewing a new town out of 6,750 Fairfax County acres, and Simon “fell in love” with the property and the prospect. He soon discovered that a few supposed assets, including easy access to the nation’s capital and the region’s new airport, were “whoppers.” Before then, though, his Palindrome Corporation bought the land for close to $13 million.

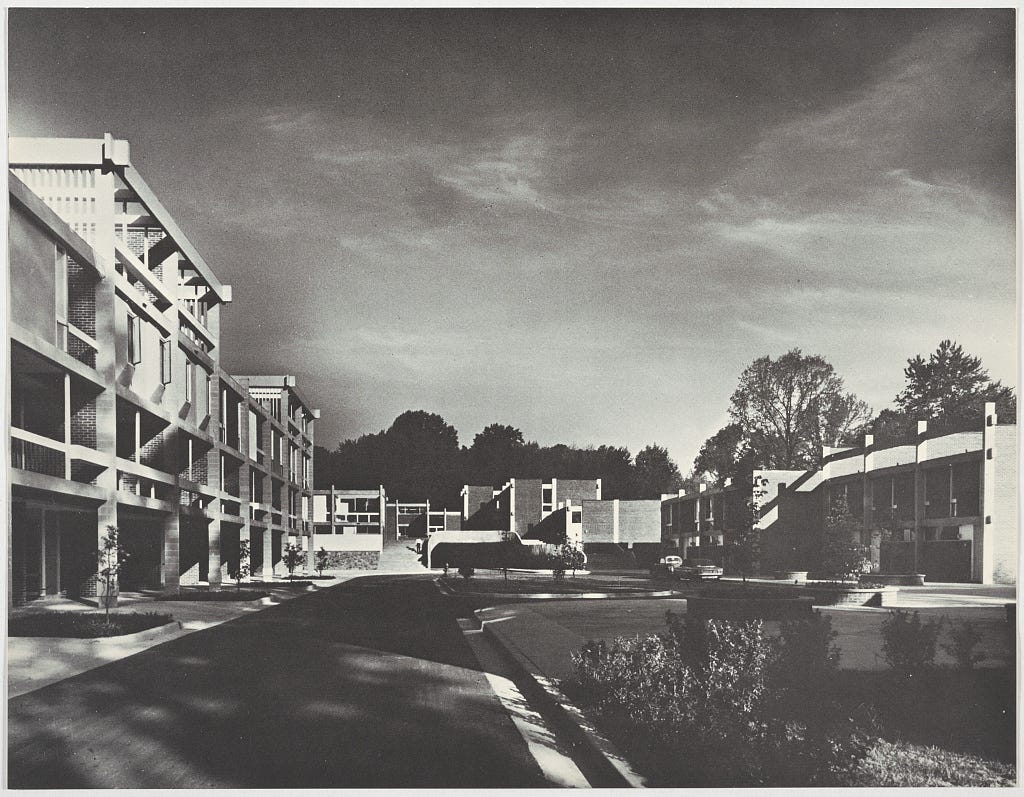

Simon knew neither the area nor this particular sort of venture well. But over the next few years, he and his team contracted architectural firms, sketched and re-sketched a master plan, and in 1962 won zoning changes to permit it. The plan emphasized housing clusters of mixed densities, anchored by seven village centers of around 10,000 residents each. Within reach would be schools, shops, houses of worship, golf courses, tennis courts, swimming pools and miles of walking paths connecting it all. The first village would surround a lake that developers would carve from the earth and name after Simon’s wife. Simon named the town itself after his initials.

Reston’s bold experiment earned it attention from likes of the New York Times and Time magazine, but not the flood of construction financing Simon needed. Part of lenders’ reluctance was that Reston was an “open” community, in a county where some still flew Confederate flags. Much of the reluctance was that, for all Reston’s publicity, its expensive concept was uncertain.

“Nobody lived there, and nobody worked there. We had to do a lot of selling of word pictures, because literally there was no water in the lake,” Veatch said.

Yet Simon resolved to have key community resources, not just the promise of them, in place by the time the first residents moved in, in December 1964. That meant a mountain of upfront costs. Gulf Oil, seeing a possibility for gas-station dominance in the high-profile new town, early that year supplied a crucial $15 million loan.

Employers began to set up shop at the Isaac Newton Square complex. Visitors attended Reston’s 1966 dedication ceremony from every continent but Antarctica. New homeowners and renters, many of them dreamers like Simon, found it wonderful.

But by the fall of 1967, that population still numbered only 2,500 people, as Reston’s sales and development failed to keep up with its bills. For more than a year by then, Gulf executives had hardened in a belief that what Simon lacked all along was not just finances but financial sense.

[Follow The Fairfax Machine on Instagram]

So, to protect its ongoing investments, and finding no other buyer, Gulf took control of the Reston project itself. In one of its first moves, it fired Simon — and ejected him from his house.

“This country’s most closely watched new community changed from one man’s dream to a corporate subsidiary,” NYT architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable wrote at the time. Her Post counterpart, Wolf Von Eckardt, thought it would “soon become en-Gulfed in mediocre urban sprawl.” The residents of walkable Reston, Veatch said, “were very much afraid” of what a gas company might do to it.

But one person who didn’t seem so afraid, whatever the indignity of his exit, was Simon.

“The planners of Reston were neither arrogant nor presumptuous enough to conceive of their task as the building of a utopia,” he said. “But it was and is hoped that something a little closer to the heart’s desire than is now available for most people would be made possible.”

From a town turnaround to a Town Center

Robert Ryan, the new leader of the new Gulf Reston, Inc., was a “brilliant” character, Veatch said, whose “thing was creating value — that was number one — and number two was listen to the market.” And the market, a Gulf analysis found, actually pointed to following Simon’s master plan. With some adjustments.

Simon’s operation, as some employees had voiced, suffered in its misjudgments of the market and its marketing, its management practices and its bloated ranks, its outside construction work, and its overpriced houses. Ryan quickly slashed staff and high-paid consultants. To revamp the slow-selling townhouses of Forest Edge Cluster, he employed an architect friend up in Boston, tweaking them to be more traditional and more affordable. According to the book “Reston: The First Twenty Years,” the first run of the new designs sold out in less than a year.

With Ryan’s more pragmatic touch, 700 Reston houses sold in 1968, triple the total of the year before. The expectations that Ryan set rose, too. In every corner of Gulf Reston, Inc., employees had a goal they kept in sight.

“They had them on their wall. They had them on their desk. I carried it in my briefcase: It was a bull’s-eye and ‘1,000’ written across it,” Veatch recalled, referring to 1,000 new Reston families a year. “And in 1969 we moved 1,150 families into Reston and never looked back.”

U.S. Geological Survey workers started to move into a new local office, and plans followed for a Sheraton Inn and a conference center site. Those entries in turn sold other employers on Reston, as did the growing range of housing, the community spaces and the trees. All the while, residents organized and pushed Gulf Reston to honor Simon’s core premise.

By the middle of 1969, Gulf dropped $35 million more into the project. By the end of that year, with building accelerating, the town’s population hit 7,500 — up 5,000 from when Gulf had taken over 27 months earlier, as recounted in “Reston: A New Town in the Old Dominion.” Gulf Reston, Inc. also built highway ramps to ease Washington commuting. By 1973, it turned its first profit.

“Gulf will be remembered,” B.R. Dorsey, the parent company’s board chairman, theorized then, “more for developing Reston and making it profitable than for anything else.”

That turned out to be premature. Gulf Reston opened a third village center in 1974, by which point the town had inspired a greener trend in Northern Virginia subdivisions. But the housing market folded with Arab countries’ oil embargo, and internal scandal at Gulf led it to back out of the real estate business altogether.

It left behind in 1978, when it sold Reston’s undeveloped land to Mobil, a realized town and a population of more than 30,000.

Mobil, from there, oversaw booms of its own. The Dulles Toll Road opened at long last in 1984. Reston Town Center, a final keystone of Simon’s original plan, opened in 1990.

Simon himself returned to Reston from New York in retirement, living in an apartment overlooking Lake Anne, his Post obituary noted. The people of Reston toasted him, until his 2015 death at age 101, as the visionary who had started it all.

No matter who had finished it.

“He had a wonderful, wonderful life and was venerated moving back here,” said Veatch, who counted Simon among his closest friends in those sunset years. “He was the ultimate winner.”

Awesome read! Thanks for putting this together

We just moved back after being in Colorado for 35+ years. Living in a high rise apartment (The Cosmopolitan) in Town Center, which wasn't even here when I sold Real Estate in the early 80's. It's new but old Reston is still the same, including Lake Anne.