Facing doom, and playing on

The Dragons Concord in Fairfax Centre is one of the only game shops of its kind. It’s also in deep trouble.

The Dragons Concord had given its employees dire news, and it hung over Chelsea Broderick as she tried to prep her weekly horror role-playing game. Broderick, 35, was sketching her own storyline and producing her own props, part-time work that took up “too much” of her nights and weekends but that she shouldered for the same reasons her coworkers at the game shop did, too:

Because the Concord was paying them to run expansive tabletop campaigns, something that few shops anywhere in the country would. Because, for three or four hours in Fairfax, that meant game masters like Broderick got to bring their imaginations to life and strangers together. Because, as she put it, each game session felt like “giving people a treat,” like “a little present I get to give people in my own way every time.”

But by the time Broderick and her players gathered for their Call of Cthulhu night last week, Dragons Concord owner Michael Gruver had announced the shop’s news publicly on its Discord server. The Concord, which had just passed its one-year anniversary, “has been steadily growing every month,” he wrote, but it wasn’t making enough to cover its expenses. Its savings were “exhausted.” If it couldn’t secure additional funding, it would shut down effective Aug. 31.

“I’m reaching out to all of you now,” Gruver said, “to help us avoid having to close the store.”

The Concord was a unique small business with what appeared to be the most common of cash-flow problems. But Gruver, a former Green Beret who lives in Tennessee, had gone to extraordinary lengths behind the scenes to save the store. Even last week, he emphasized, he was not giving up on the Concord or the community it had grown.

And, even then, it was still growing. Broderick’s Call of Cthulhu game welcomed a new player that night, which was a start.

What the Concord needed now was for players like him to come back.

I.

Role-playing games have boomed in popularity in recent years, but making a profit on them is tricky, said Tom Haid, the owner of Curio Cavern, a shop that started in Springfield in 2011 and has expanded since. Unlike trading cards or games like Warhammer 40K, tabletop RPGs like Dungeons and Dragons require buying only some dice and maybe a sourcebook to play for years.

“From a player standpoint, RPGs have really enticing low-cost, low-overhead appeal,” Haid said.

Curio’s original Springfield location has volunteers run D&D games on Mondays and charges $2 to play, a conceit to bring people into the store, not to drive profits itself. A local group hosts D&D sessions down the street from the Concord at Pair O’ Dice, but the shop doesn’t schedule and organize the games, an employee said.

“I told my wife and really convinced her: ‘We’ve got the money. Why don’t we make our own tabletop gaming center and solve the problem for ourselves and for as many other people as we can as well?’”

Those models left an opening for a richer tabletop experience, Gruver thought. He had started playing D&D with friends as a youngster, “Stranger Things”-style, “a bunch of weirdos in a dark room rolling dice.” He and his wife, Amanda, met playing Werewolf: The Apocalypse. When he retired from the military in 2020, he got back into tabletop games but found that the quality of online campaigns charging $50 a pop was hit-or-miss.

“I told my wife and really convinced her: ‘We’ve got the money. Why don’t we make our own tabletop gaming center and solve the problem for ourselves and for as many other people as we can as well?’” Gruver recalled in a phone interview.

The couple, then living in Woodbridge, spent six months “kind of stewing on it,” he said, devising names and a business plan for a shop that would vet its game masters and do tabletop better. They found a space in Fairfax Centre, a tucked-away former office for a telecommunications company, and began a lease in November 2022. They took out a $186,000 loan that covered store construction, furniture, and a back corner of retail stock.

But the Concord didn’t open until the following June. By that point, the marketing and decorating budget had been “eaten up by delays,” said Sean Crane, the Concord’s do-everything store manager, who had joined as its only full-time employee.

The shop started hosting events and free drop-by hangouts, launched paid campaigns in three themed gaming rooms, advertised where it could, and interviewed and contracted “Storytellers” like Ron Power, 50, whose parents first got him a D&D box set when he was 8, and Broderick, who got into D&D in 2017.

The store also started cultivating loyalty. Ellen Turner, an IT consultant who lives in Annandale, was an early Concord convert. As an introvert, she said, she felt more comfortable trying out tabletop games at a dedicated store, so she waded in with the Concord’s Friday board-game nights and with a one-session D&D adventure. She now plays in five biweekly D&D games at the store, befriending both the staff and customers with whom she’s gone to the Maryland Renaissance Festival, Scottish highland games, escape rooms and people’s homes for dinner. Dragons Concord visits became Turner’s routine, a place “to step away from computers for a couple of hours” to connect with enthusiastic people, a place where she “had a whole new world of games opened up to me.”

She worried from the beginning, she said, about whether this business that brought her and her new friends so much joy could be sustainable.

II.

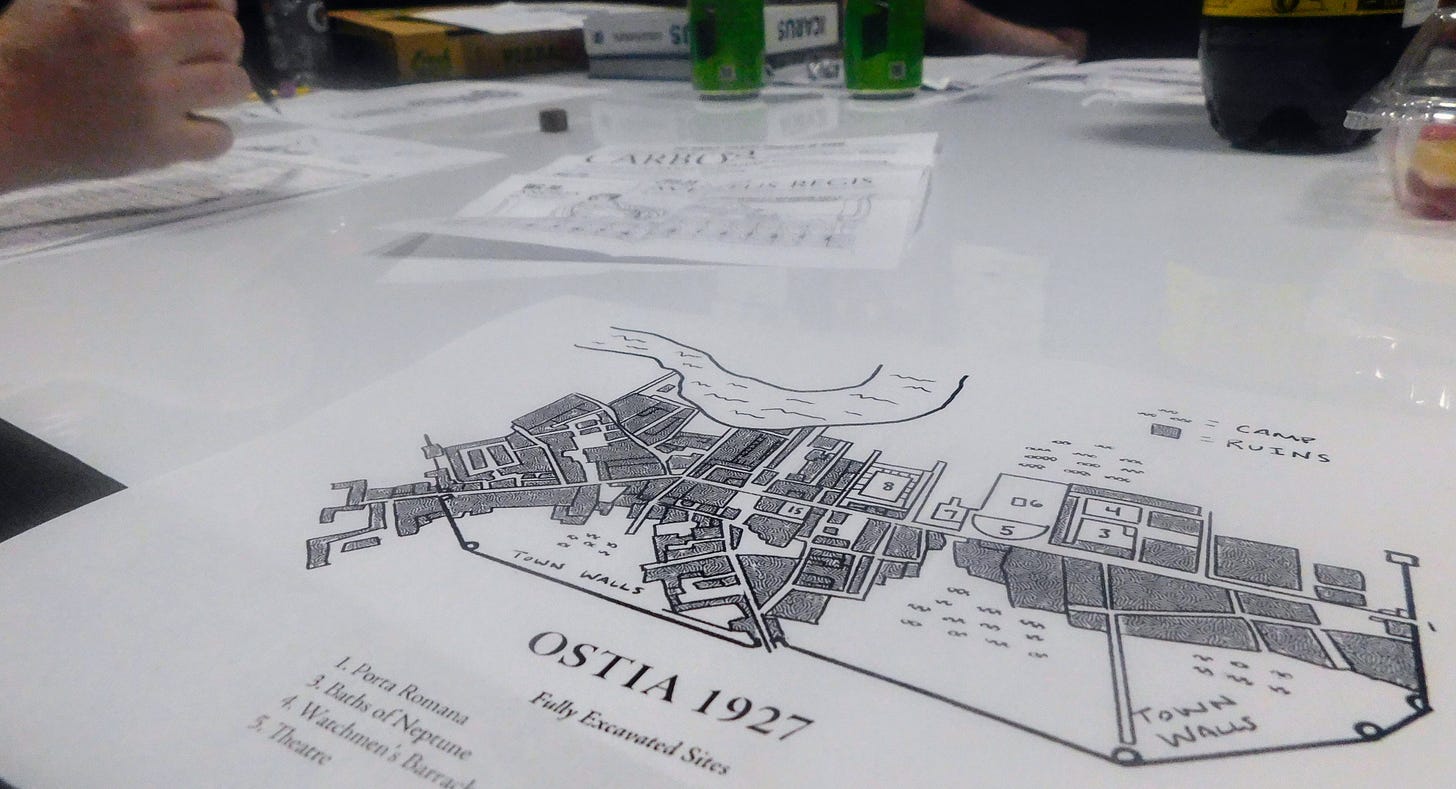

The Concord’s Speakeasy Room, where Broderick runs her 1920s-set horror campaign, had ethereal music drifting from the speakers and jelly candy, a Pizza Boli’s pie and a bottle of Russian soda on the table. Call of Cthulhu is an investigative game, and Broderick, a graphic designer, likes giving her players “something tactile” to immerse them. For this session she handed out maps and a flier for an eerie Italian theater festival, but in the past she’s used tea to age paper into old parchment, shaken up water with flecks of coconut to mimic a jar filled with worms and, once, bought seven fake tongues off Amazon.

“Which is a random amount,” she said, “but it was just as much for two tongues.”

It’s hard to wrangle any group of adults for a weekly tabletop game, especially as friends get older and start having kids. But with this Dragons Concord game, the players agreed in August that they would pick a day and stick to it “in perpetuity,” said one of them, Ian Barr, an Air Force employee from Arlington.

“So, Wednesday is that day,” Barr said. “This is the thing that happens on Wednesdays.”

Over three hours this Wednesday, Broderick answered and supported her new player throughout, just as the Concord looks for when it interviews prospective Storytellers, a multiround process that includes running a game. She inhabited a jumble of characters for her players to interact with: wealthy train passengers, “sloshed” actors, a ghostly young girl and an actress Broderick portrayed with widened, unblinking eyes, tilting her head like a person possessed.

Her players shook their heads in dread. “Are we all gonna die?” Barr asked.

The thing about Call of Cthulhu is that it’s not a heroic fantasy, like Dungeons and Dragons often can be. You’re not a holy warrior or a magnificent wizard, just an ordinary person confronting living nightmares with whatever courage and guile you can muster. Broderick said she wants her players to find meaning in that.

“The real world can get pretty depressing, and you can’t grapple with it in any real way sometimes,” she said. “That feeling like you do have some agency in it, in confronting horrific things in a safe environment here that would not be possible in the real world — I find it very fun and cathartic to do.”

III.

The real-world trouble began, Michael Gruver told me, months before he and his wife opened the Concord. To secure the lease at Fairfax Centre, they needed to show more funding. But to get that funding, they needed to take out the $186,000 loan. “And that was not a great way to structure it,” he said.

The store’s monthly rent, taxes and maintenance cost around $8,000, Gruver said. But add to it the $4,300 installments on that loan plus pay for Crane, hourly employees and Storytellers, who split the revenue from their games with the store, and the Concord has bills totaling around $22,000 monthly. Those costs have begotten greater ones.

“Up until December of this year, we had a five-acre wooded lot in Woodbridge with a beautiful house and a creek running through the backyard, that we sold to keep the business going, because that’s what needed to be done,” Gruver said. “The month before that, I cashed out my daughter’s entire college savings, to make sure I could pay payroll through Thanksgiving. I’ve dumped every spare dime that I’ve had since [last] June into making sure that this thing can keep going and grow, and that’s definitely affected our ability to go on vacations and do stuff as a family.”

Gruver, 42, served 20 years in the U.S. Special Forces, he said, deployed to every combat zone in the Middle East. The first eight months of running the Concord were the most stressful period of his life. It took an investor’s intervention in November to save the company a first time.

And yet: People have been “coming together and finding this center as a major focal point of their lives and their happiness,” Gruver said. “And I just can’t quit that.”

Give it one more year, he believes, and he could make it work. The Concord is scaling up with Storytellers now, cutting down its hourly labor, and running a GoFundMe and a commercial in movie theaters that’s generating website and in-person visits. One Storyteller’s wife is looking into what it would take for the shop to partner with a nonprofit. And Gruver is getting a tax refund soon that will bring in about $30,000, he said.

If the Concord has enough funding that it looks viable to keep the business open through December, he’ll pour it in. If not, he’ll put it into payroll and liquidation — and, as soon as he can, reopen with a new storefront and a reputation already constructed.

“I am an eternal optimist,” Gruver said. “When I’ve decided something is going to happen, it happens.”

So, here’s what he’s decided: If the Concord can get big enough, it will publish original adventure modules. It will make the in-store games free and make its money from running role-playing games to facilitate team-building, leadership trainings and therapy. It will spin off franchises, bringing its model to other communities around the country.

“Semi-jokingly, I’ve been telling employees, if we get to a point where all that is working, I want to build a castle and have a year-round Ren Faire-type thing somewhere in the central part of the country, like Tennessee, somewhere where it’s nice and pretty, mountains and forest,” Gruver said. It would be a showcase of blacksmithing, leatherworking, “all those skills that people get into because of role play.”

He lamented that those dreams could crumple “not because the idea isn’t valid or it isn’t workable, but because I ran out of money and didn’t learn the lessons I needed to learn fast enough.”

“Twenty years from now, I’m going to be 62,” he said. “And that’s still young-ish. But that means spending the next 20 years of my life fighting to make this thing work and not really enjoying my twilight years.”

I told Gruver that sounded like a lot to sit with.

“Yeah,” he said. “But if it’s worth it. And it’s worth it if we can make it work, and that’s where my optimism is.”

IV.

Broderick ended that Wednesday night’s session with the characters entering a necropolis outside Rome, the smell of death all around, and her new player stayed afterward to chat. He said he had seen Gruver’s Discord message.

“It’s just a real shame that it feels like everything is going really well and better than ever before, but there’s just been some other setbacks that have happened,” Broderick said.

The new player said he was “trying to patronize how I can.” Already, he had signed up for two other games with two other Storytellers. He was planning to sign his son up for the Concord’s July camp. He had enjoyed his intro to Call of Cthulhu.

“See you next week,” Broderick told him as he left.

It was storming outside as she went to drive home, too. It had been for a while, actually, a hard deluge that had pierced the week’s heat wave.

It was funny, though: Inside that room, a hundred years and a continent away, you couldn’t hear a thing.