Bridging U.S. divides, a dinner at a time

Worsening polarization is splitting families, friends and neighbors. Can this Reston project help curb it?

Michael Graham arrived at the Reston community center 43 minutes before his latest attempt to heal the discourse of the nation, wearing the three-day stubble of a young dad and the smile of a dogged American optimist.

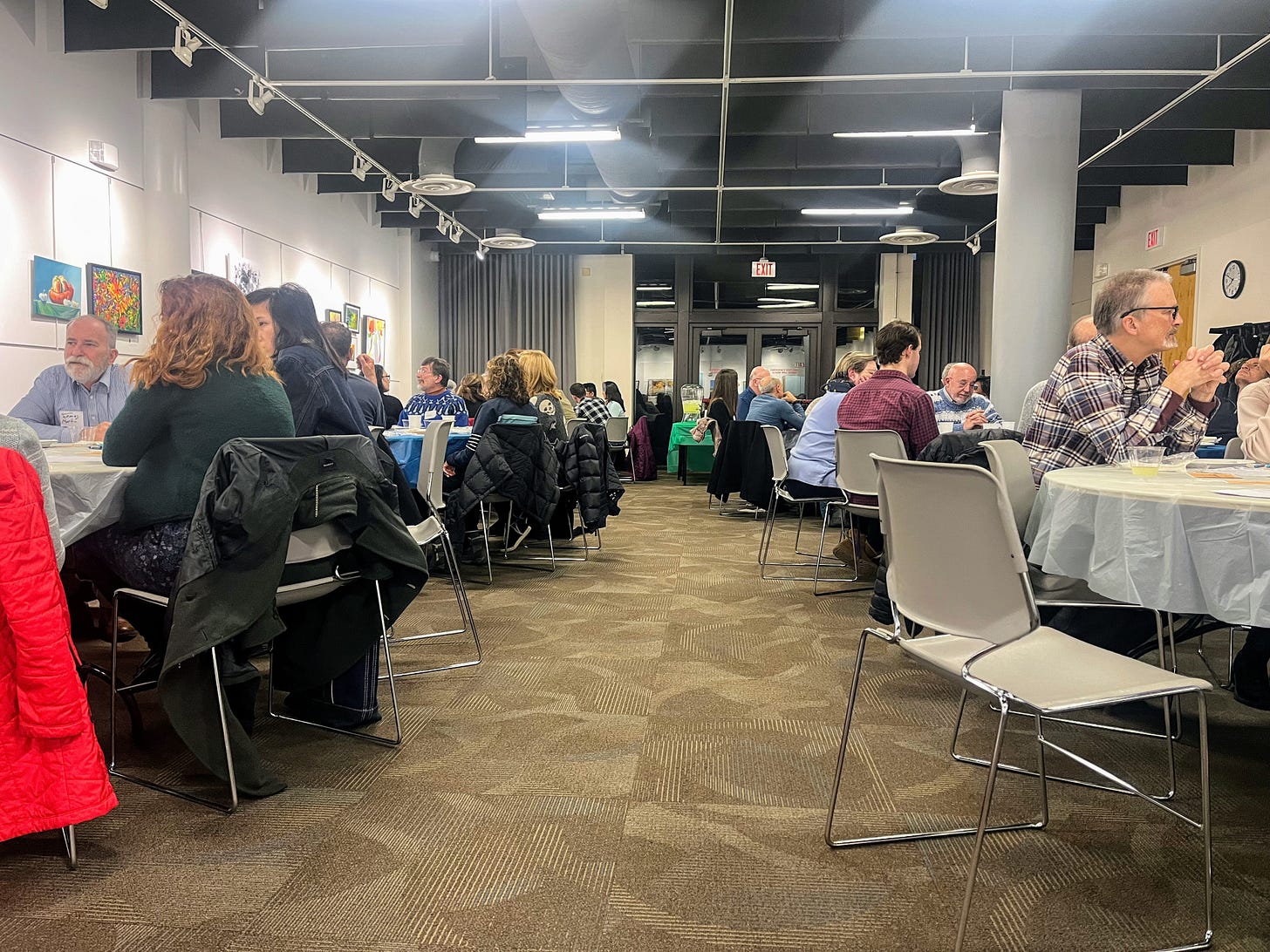

He greeted the participants as they entered — more returning faces this time; that was good — and, before their pasta dinner was served, took the microphone to explain the night’s program.

“Families have been split apart” by worsening polarization, Graham said, and the six tables full of people in deep-blue Fairfax County seemed to agree. “There are so many important issues that we should be talking about, but we can’t even get there, because we can’t sit at a table and sit across from each other and have a civil conversation.”

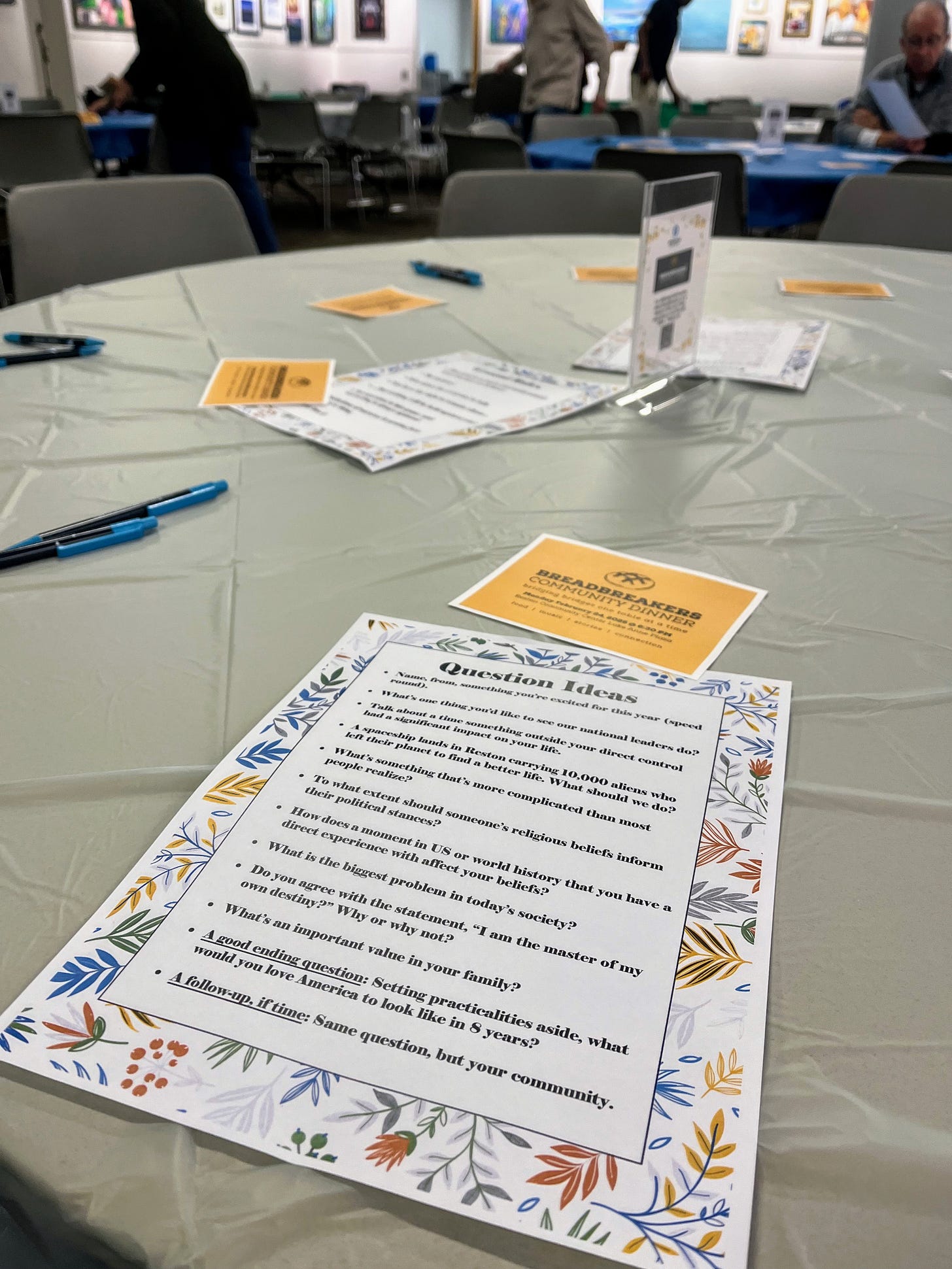

BreadBreakers dinners like this one, he said, were their chance to “practice.”

Graham, 31, launched the project a year ago within Restoration Church of Reston, and in September he took the dinners public, aiming to stoke a movement of depolarization through connection. In that mission, BreadBreakers joined groups like the People’s Supper — which trained Graham and his team — and Braver Angels, a nonprofit founded after the 2016 election to “bridge the partisan divide and strengthen our democratic republic.”

Graham didn’t know about Stanford University’s Deliberative Democracy Lab, but BreadBreakers is a lot like that, too. Before the 2020 primaries, its researchers convened a 500-voter event in Texas called “America in One Room.” Participants, they found, moderated their stances after deliberating together over issues like immigration, and dislike between Democrats and Republicans dropped.

“People are hungry” to turn down the temperature, Graham first told The Machine in late November. But the folks who seek out the kinds of conversations that BreadBreakers offers are “definitely an anomaly,” said Alice Siu, the associate director of the Stanford lab and a senior research fellow. “It’s hard. I think it’s really hard to actually take action to engage with people, so I think a majority of people think that it’s a problem, but we don’t really do anything about it.”

At the community center in Reston, Graham warned his participants that it would indeed be hard, that past BreadBreakers dinners had seen “emotion,” “conflict” and “tears.” By night’s end, they would see all three again.

But “our goal is to learn and understand, not convince or debate, so we are going to lead with curiosity,” Graham said. “We are going to have our own views. We are going to have conflict and some disagreement, but I encourage you to, when you hear that thing you disagree with, ask them questions about it. Try and really understand their perspective, where it’s coming from, why they believe what they believe.”

He told the participants to share the time, that they had “the right to remain silent” if they so chose. He told them that success would mean “learning one new thing.”

He told them all, five days before Donald Trump’s re-inauguration 19 miles to the east: “Have fun.”

Trial runs, conflicts and ‘hope’

The idea for the dinners started over breakfast, one between Graham and Restoration Church Pastor Daniel Park at IHOP in the summer of 2023.

Graham, an industrial engineer, had watched with dismay during the pandemic as the country briefly rallied together, then fractured back apart. He grew up in Michigan with friends and family across the red-blue spectrum, and he told Park that he’d had “bridges burned” by political division and polarization, Park recalled. Graham wanted the church to be part of a secular solution. Park agreed.

Facilitator trainings and Restoration-only dinners followed, and congregation members embraced them. In September, Graham brought the dinners to the public, mostly single-table events with occasional larger ones, promoting them through Meetup.

Trump’s share of the vote in Fairfax County ticked upward in November, and Graham, who voted for Vice President Harris, hoped that some of Trump’s supporters would show up, so that “the people who see each other as enemies” could cut through the caricatures.

Dionne Spriggs, 59, is one of those who decided to go, because she wanted the same thing.

“I think people have this idea that everyone who voted for Trump was this racist white guy,” said Spriggs, a Black woman who grew up in New Orleans and lives in Falls Church. She’s been to four or five BreadBreakers dinners by now, she estimates, determined to show through dialogue that Trump voters are not “a monolith.”

The dinners’ topics have spanned Trump’s potential impacts, media consumption, where participants feel the most belonging, optimism and pessimism, the economy. A few conversations about God with one regular attendee, a zealous non-believer, have challenged Graham’s faith as much as strengthened it, he said. Maria Bissex, 45, a theater-costume designer from McLean, has spent dinners at turns allying with one Trump voter during a fierce conversation on abortion, which she strongly opposes, and sparring with others while defending the work of immigrants.

“To me, I feel like it’s success if even a handful of people are listening to each other. Will that change the world? No, but it still is going to change the circles those people are in.”

She left the last BreadBreakers dinner she attended, a month after the election at Kalypso’s Sports Tavern, feeling frustrated and judged. She signed up for the next one anyhow.

“To me, I feel like it’s success if even a handful of people are listening to each other,” Bissex said. “Will that change the world? No, but it still is going to change the circles those people are in.”

Graham gathers feedback cards after each dinner to gauge any immediate changes, and he does find them, even if small. “I came with a high level of anger,” one card read. “I am leaving with a better understanding of how other viewpoints feel.”

“What I came with: fear and sadness,” read another. “I am leaving with peace and hope.”

The fear and despair came up often. At the Kalypso’s dinner, the last one of 2024, Spriggs and other Trump voters made a majority at the table for the first time. Graham wondered whether that meant some on the left were “planting their gardens,” “living their life” and tuning politics out.

‘I have been underground’

At her table at the community center, facilitator Lisa Belt opened up the conversation and confirmed as much.

“I’ll put it out there: Things in November didn’t go the way I had hoped they would go,” began one participant, who said she’d recently retired as a head of school. “I have been underground since then. I used to be a CNN addict. I haven’t watched or listened to any news since November the fifth. I need to get better at talking to people who may not feel the way I feel, and so I thought this would be a good way to do that.”

“I’d like to piggyback, if I may,” said the woman to her right. “The recurring theme that I’m seeing and hearing is ‘making America great again,’ and I was not liking the way that’s being depicted in so many different ways. And I felt like this was one way that I could actually work to make America great, by starting to improve and increase dialogue and being a good example for others.”

And so the table discussed the “topsy-turvy” state of the world, the all-things-considered stability of the U.S., Trump’s potential impacts on immigrants, the white working-class vote, class mobility, and what many saw as a national shift in decency.

“I felt like this was one way that I could actually work to make America great, by starting to improve and increase dialogue and being a good example for others.”

The piggybacker confided that her half-Japanese daughter, who lives in rural Louisiana, had recently spoken with her about buying a firearm. “I don’t want my daughter living in a country where she feels has to carry a gun for her safety,” the woman said.

A table over, they were discussing — from Graham’s list of questions — a time when “something outside your control had a significant impact on your life.” A woman in a striped blue sweater shared about her father’s covid-19 infection, stroke and death, “the worst year of my life.” A shaved-headed veteran shared about coming back from Afghanistan with PTSD, how his loved ones noticed it in him before he did in himself, how he had gone to therapy and connected with other veterans and found healing.

“When you start sharing, you realize that you’re not alone,” facilitator Nora Lynch said.

The woman in the blue sweater noted that “we’re all people,” with “good and bad points.”

“That’s the key,” Lynch said. “And sometimes I think people forget that.”

‘This is a practical thing’

Graham wants to make this his job in the future, to help people remember. He has spent vacation time planning for BreadBreakers; has spent time after putting his 2-year-old son to bed sending emails or holding meetings; has spent free time on weekends, too, when he and his wife, Jess, a nurse, divvy up caretaking. He has also gained efficiency, and confidence, with experience.

When BreadBreakers went public, Jess Graham recalled, Michael would drive home to Sterling less sure of how a dinner went. Now, she said, he comes home “energized,” going: “Oh my gosh, it was amazing! We talked about this, and this person was so unique …”

Michael Graham is, yes, as excitable as a tee-ball coach, Hardy-boy earnest. But he’s not naive. BreadBreakers’ goal is not to “agree to disagree,” he insists, nor to provide a tolerant forum for “abhorrent views.” It is, as he casts it, an investment in trust.

“It’s radical to show love and to show that you see that other person who has a view that you think is absolutely terrible as a human being, and to show them that I’m willing to sit here,” he said. “I’m not going to agree with much you say, but I’m willing to at least hear you and treat you as a human worthy of engaging. I think you have to do that if you want to actually improve things, so it’s practical.

“This isn’t some Kumbaya, feel-good, hold-hands [thing]. This is a practical thing that is a necessity.”

It might be even more of a necessity, he thinks, in politically split Michigan, where in the fall he ran two BreadBreakers tables at his hometown church. Graham wants to expand, but for now he has enough to handle, including making the large dinners in Reston monthly.

Other challenges are built in. Graham wants conversations to be factually grounded, but he and his facilitators can’t fact-check all the slush on climate science and other things that participants might throw out in real time.

In Stanford’s deliberations, participants receive vetted information on each subject in advance, which helps establish trust, said Siu, the DLL associate director. From there, she believes storytelling and emotion are “the crux” of what changes minds — like the story of someone losing their job because of certain taxes, or personal climate change impacts — though researchers can’t draw a clear line.

In any case, it’s clear that minds do change: Follow-up surveys have found lasting shifts in deliberators’ voting intentions (from Trump toward President Biden), in their media consumption, and in “their willingness to talk to people who were different from them,” Siu said.

One person who has faith in BreadBreakers’ deliberations is its zealous non-believer. His name is Albert Halac. He’s a retired immigrant from Argentina.

Halac, 85, reads a ton and fears no argument, and he suggested in a phone call with The Machine that the dinners could have greater impact if they involved “more teeth,” less just listening. But he appreciates, he said, how Graham and Restoration have kept the dinners secular, whatever their spiritual differences.

“It will have a long-term effect. I’m sure,” Halac said.

Why is he sure?

“The drive,” he said, “of this man, Michael, and the church to do this.”

A welcome problem

Just before dessert at the community center, Graham asked for a few participants to share their reflections with the group. The last comment went to a Black man in suspenders, who was at the table Graham had moderated. There had been “contentiousness” in their discussions, he said, but he was leaving with “more compassion.”

A band called the Peacemakers then led the room in a truncated rendition of “Lean on Me,” and more people than you might expect joined in. Graham took the microphone back after for a few closing messages. When he spoke of the “movement” they were trying to build, a movement that was building right there, applause rained. And people stayed.

Halac and a woman in her 30s stayed to argue, to her confusion and their mutual exasperation. The mom of the rural-Louisiana daughter stayed to chat with her tablemates, after thanking a flight attendant for what he had shared. She hoped to see him at a future dinner, she said, so she could follow up.

Graham stayed later than he came early, talking with Park and seeing off the night’s participants and hearing, from many of them, that they’d be back and tell their friends. The cleaning crew had begun its work by the time that Graham shared a reflection of his own from the night — that his table had been “the hardest” he’d led so far. But he felt, again, “energized.”

That contentiousness, he explained, had concerned a BreadBreakers first-timer, a Trump supporter who had come in hot and ticked the table off. He wasn’t its only Trump voter; the man in suspenders was, too. It was more an issue of, well, civil dialogue.

Other participants told the man they didn’t feel respected in the way he was talking to them. Graham reiterated the ground rules. Then, he led with his own curiosity: Why did you ask that question that way? What have you experienced in this area, as someone who’s felt the heat of your neighbors yelling at you because you had a certain political belief?

Looking to turn down the national temperature, Graham had gotten a flamethrower right in front of him.

“I spent months and months and months trying to figure out: How am I going to get people like him to come to these types of dinners?” Graham said. “That tells me that the numbers are growing large enough that they’re finding their way in, whether through invite or through chance or just that one little spark of, ‘Eh, why not? Let’s give it a shot.’”

Graham sought the man out when the dinner was over, asked how he felt.

He told him: I hope you come back.

Ryan, I am going to miss your talent and your vision as you express it here. Your editor's eye for the timely and important topic is unerring. I look forward to seeing what comes next, and to following the BreadBreakers efforts.

Hi Ryan, excellent piece! How well have you captured the dynamics of these meetings! If the members of our BreadBreakers group share your note, I am sure it will help us grow and spread our message.

Thank you for portraying us so well.

Albert Halac